Tropical rainforests - photographing under harsh conditions

Uploaded 12. July 2011Tropical rainforests all around the world offer an immense amount of photographic possibilities for every nature photographer and wildlife enthusiast. The sheer mass of invertebrate critters and exotic plants constantly overwhelms macro connoisseurs, while enormous trees and rapid waterfalls delight landscape photographers. Others chase colourful birds which roam the treetops, follow nocturnal calls of courting amphibians or patiently wait for seldom-seen mammals.

The abundance of these photographic subjects entices professional photographers and keen amateurs alike and consistently draws them to the world's spectacular rainforests. But those hotspots of biodiversity have certain downsides: low light conditions, high humidity and limited accessibility constitute harsh conditions for photographers. While to some degree this is part of the appeal of rainforest photography, here are a few points to consider before you head off:

The Light (or lack thereof)

On my first trip to a rainforest I was amazed by all the macro opportunities around me, but at the same time genuinely shocked about the bad light conditions. The dense canopy absorbs the large majority of sunlight, leaving the understorey in a gloomy shade. Consequently, this lack of light results in prolonged exposure times and thus potentially shaky images, for which you can compensate in two ways:The first is to use a sturdy tripod whenever needed (i. e. most of the time). Since many interesting subjects are crawling on or close to the ground, one of those tripods with which you can lower down your camera all the way to the dirt have a big benefit. You can also consider bringing a light bean bag for this purpose. But even if you can prop your camera long enough to get a proper exposure, movement of your subject will easily spoil the picture. Far too often a falling drop will shake a flower or an interesting critter will just hop away.

The second way to deal with low light is to use a flash. By simply bringing your own light source you are independent of prevailing light conditions. You're also much more mobile and not as stationary as when using a tripod and therefore able to stalk a moving bug or follow a hopping frog more easily. The downsides of using a flash are possible reflections and strong shadows, so think of a diffuser or bouncer for your flashlight.

The image on the left was

taken with a tripod; the cooperative frog held still for

the entire 4 sec exposure.

The image on the right shows an agitated strawberry poison-dart frog and was shot using a flash and a self built diffuser.

The image on the right shows an agitated strawberry poison-dart frog and was shot using a flash and a self built diffuser.

The water (how to stay dry)

Depending on which rainforest you want to visit, you may find regional differences in seasonality. Some parts of the tropics have defined wet seasons or monsoons, others no significant changes in precipitation throughout the year. But all tropical rainforest feature a high degree of humidity and a big likelihood to get caught in torrential rain - so prepare your gear accordingly. I'm currently using a Lowepro Allweather backpack, which I believe to be reasonable waterproof. But in the tropics, rain can start at an amazing speed with an impressive amount of water pouring down on you and your camera. I therefore like to carry a bunch of thin trash bags along with me, which I can quickly use to store my gear in or simply pull over the whole camera and tripod setup.While exposing your camera to excessive rainfall can be avoided, the high humidity in tropical rainforests is not as easily to evade. Damp air has the ability to damage electronics and rapidly grow mould in lots of places. I use a combination of silica gel and regular maintenance to prevent this.

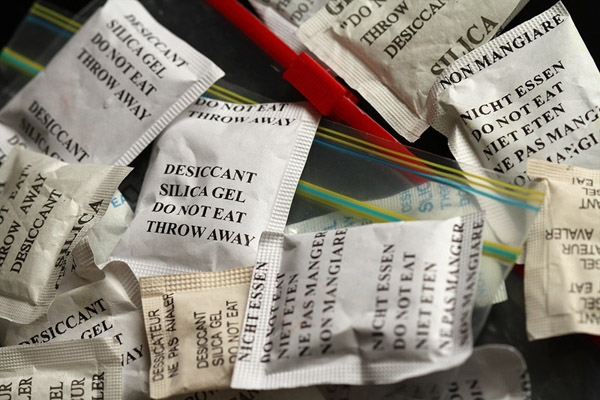

Silica gel is a desiccant for absorbing moisture - small sachets of it come with deliveries of clothing or electronics. You can order dessicant online or just ask local shop venders, who have heaps of silica sachets and usually give it away gladly. I use small, Ziploc-style bags with a few silica-packs inside to store sensitive batteries for cameras and flashlights in order to keep them safe from corroding levels of humidity. Additionally, I like having some sachets of dessicant loosely in my camera bag to control air moisture.

Sachets of Silica gel and airtight plastic bags help you keeping small electronic gear such as batteries dry.

A more serious threat to your camera gear is fungus. The combination of high temperature and humid air consitutes optimal conditions for mould. Once within a lens, fungus is very hard to remove and the infected item should be isolated quickly to prevent further proliferation. The best countermeasure to avoid this is letting your camera dry in a low-humidity environment as often as possible.

Although all this might sound quite pessimistic, it's important not to be over-careful with your gear. Keep in mind that your camera is a tool which you specifically bring to the rainforest to shoot stunning pictures. A still shiny camera will not compensate for missed photo opportunities and in the end, that's what it's all about, isn't it?

Before you leave

The majority of tropical rainforests are pretty remote and

it is exactly this remoteness and limited accessibility that

make the jungles so interesting and wildlife so abundant.

But once you're there, it might be hard or even impossible

to buy stuff you forgot or get new batteries, so prepare

your trip beforehand:Bring a healthy amount of camera batteries if you cannot be sure to be able to recharge your stuff regularly. Have enough CF/SD memory cards with you and think of a backup strategy (DVDs, external harddrives) during your trip. Bring enough AA batteries for your flash since regular use in dark rainforests will drain them rapidly.

Besides all your camera gear, don't forget to equip yourself accordingly: fast-drying clothing or even an umbrella might be better suited against constant rain than a poncho, which so many tourists wear but only keeps heat and humidity trapped inside. Use dark brown/greenish colours as camouflage for wildlife photography. Since night falls early (around 6 PM) in the tropics, a strong headlight helps immensly if you want to search for nocturnal critters and while keeping your hands free to operate your camera.

Longer hikes to remoter areas have the benefit that you will find more wildlife and pristine nature than in touristy places, but it also means that you usually have to carry all your stuff to get there. For longer journeys and bigger hikes, weight can become a significant tradeoff - carry an extra two pounds or leave the lens at home? So don't bring everything you might use, only carry what you definetly will need. One of these things you're surely going to need is insect repellent; expect to encounter hordes of blood-thirsty mosquitos, especially during nighttime. Remoteness also means that you're pretty much on your own in case something unpleasent happens to you. It is therefore advisable to bring basic first aid equipment and treat cuts, bites and abresions immediately to prevent inflammation. Although most animals will flee if you come too close, be keep in mind that some of them can and will defend themselves if the feel threatened. This is especially true for snakes, spiders, bees and ants. Some of these can be pretty dangerous, but just treat them with respect and you can take stunning images of their natural elegance.

Have fun exploring tropical rainforests!

Hognosed pitviper,

Costa Rica